|

| Image taken from the cover of the RCA single release of "Golden Years" |

Whenever someone finds out I'm a fan of David Bowie, I usually get asked: "What's your favourite song?"

I think they assume it will be a difficult question for me to answer. But actually, it's pretty simple. The Bowie era I favour may change day-to-day, but my overall favourite album stays constant: Station to Station (1976). And although I love each song for different reasons (and I believe they work best as seen in the cohesive whole of the album), I can't deny that the song I play the most is "Golden Years". It's also my ringtone.

Today, I want to make an argument for why this song above all others is my favourite work of Bowie's.

To give you a flavour of the competition I'm pitting this song against, "Golden Years" is compared to the likes of: "Changes", "Life on Mars?", "Space Oddity", "Ziggy Stardust", "Rebel Rebel", "Heroes", "China Girl", "Moonage Daydream", "Jean Genie", "Fame", "Ashes to Ashes", "The Man Who Sold the World", "Fashion", "Let's Dance", "Starman", "John, I'm Only Dancing", "Young Americans", "Loving the Alien", "Modern Love", and "Sound and Vision" just to name a few Bowie hits - never mind his other work on collaborations like with Queen on "Under Pressure" and productions like Iggy Pop's "Lust for Life". So to claim that "Golden Years" is The Best David Bowie Song is a pretty tall order.

To begin with, the origin of "Golden Years" doesn't initially make it stand out. Bowie claimed the song was initially written for Elvis Presley (with whom he shares a birthday and a pivotal role in shaping rock music and popular culture). And this practice of Bowie initially attempting to write songs for other musicians to perform (before doing them himself) was typical of his work. As he stated in an unaired "60 Minutes" interview, "I was never particularly fond of my voice. I thought that I wrote songs and wrote music and that was sort of what I thought I was best at doing. And because nobody else was ever doing my songs, I felt, you know, I had to go out and do them."

The vocal work of "Golden Years" certainly seems to confirm this original intent. At "Pushing Ahead of the Dame", (an excellent one-shop Internet source for all things Bowie), Chris O'Leary elaborates on the claim when he writes, "The earlier rock/R&B influences seem fitting when you consider that Bowie wrote the song with Elvis Presley’s vocal range in mind..., though apparently Bowie never officially submitted the song to Elvis, as negotiations with Col. Tom Parker had petered out." But whether or not it's true that Bowie wrote it for Elvis, I'm very glad The King never ended up pilfering the fantastic song.

Because although the origins don't make "Golden Years" special, the musical content of it does. It's catchy. It's funky. It's fascinating. The early rock and R&B influences are particularly striking. In The Complete David Bowie, Nicolas Pegg states:

Just as "Rebel Rebel" had offered a furtive farewell to glam and an urepresentative preview of Diamond Dogs in early 1974, so the immaculate funk of "Golden Years", preceding the release of its parent album by two months, is more of a piece with Young Americans than with the steelier musical landscape of Station to Station. In common with much of the earlier album, its roots in American soul-pop are easily discernible: Carlos Alomar's riff owes a debt to "The Horse", a 1968 US one-hit wonder by Cliff Nobles & Co, while the multi-tracked vocal refrain recalls The Daimons' 1958 single "Happy Years". Co-producer Harry Maslin recalled that "Golden Years" was "cut and finished very fast. We knew it was absolutely right within ten days. But the rest of the album took forever." Early in the sessions the album itself was to be called

Golden Years.

David's old friend Geoff MacCormack, credited on Station to Station as Warren Peace, assisted with the song's complex vocal arrangement. "He wanted it quite loose, casual," MacCormack later wrote in his memoir. "I loved what he'd already done in terms of its flavour, especially the 'Cum b-b-b-baby' bit. I extended the idea by dropping the 'golden years' phrase the second time around and preplacing it with a long, up-and-down, swooping 'gold' phrase and adding 'wah, wah, wah' on the end. David loved it and let me fiddle around with the 'run for the shadows' section as well. When we came to record the backing vocals for the song David lost his voice halfway through, laeving me to finish the job. That meant I had to sing the series of impossible high notes before the chorus, which were difficult enough for David but were absolute murder for me."

And O'Leary confirms this account of creating the single at his blog, stating:

Bowie had written some of “Golden Years” in LA in May 1975, before he left for New Mexico to spend the summer filming The Man Who Fell To Earth. His friend and collaborator Geoff MacCormack, for whom Bowie played an early version of the song, suggested the wAH-wah-WAH tag after each chorus phrase. The opening guitar riff’s been claimed by both Earl Slick and Carlos Alomar, Station to Station‘s dueling guitarists.

Its influences seem to have been “Broadway” songs: the Drifters’ “On Broadway” (Alomar recalled Bowie playing “On Broadway” on piano and putting his own vocal hook into it: “they say the neon lights are bright, on Broadway…come get up my baby”) and Dyke and the Blazers’ “Funky Broadway,” from which Slick said he pilfered some of the guitar riffs.

[...] The final track offers layers of hooks and pleasures, from Dennis Davis’ expert timekeeping and the various percussive fills pushed up in the mix (handclaps, castanets, snaps, shakers) to Bowie’s rich, cool, layered vocals...to the continually dueling guitars—one mixed in the right channel playing variations on the opening riff throughout much of the song, while the other keeps a shimmering rhythm going in the left channel, and eventually crafts a three-chord riff (MacCormack’s “wAH-wah-WAH”) at the end of verses/choruses. (An acoustic guitar, possibly Bowie, is mixed in as well).And indeed, primary sources Carlos Alomar and Earl Slick further confirm both authorial accounts in this lovely interview where they also demonstrate the progression of the fantastic guitar riff:

Although "Golden Years" may never reach the same level of musical innovation and renown as some of his other works, the pleasing chord changes, structural nuance, and smooth vocal work make for a fantastic track nonetheless - and the performances and legacy of "Golden Years" attest to this. As Pegg writes,

"Golden Years" consolidated David's commercial stock in American, reaching number 10; in Britain, hard on the heels of the chart-topping "Space Oddity" reissue, it made number 8. The 3'30" single edit was essentially the album veresion with an earlier fade, although the sereo spread and reverb levels differed from one territory to another; several variants have since appeared on compilations and reissues.

Some sources suggest that "Golden Years" made the occasional rare appearance on the Station to Station tour, but it is generally accepted that the song made its live debut seven years later as a regular fixture in the Serious Moonlight shows. It later reappeared in some of the early Sound + Vision concerts, and was revived once again in 2000. The song has been widely covered by artists including Pearl Jam, Loose Ends, Nina Hagen, and even Marilyn Manson for the 1998 film soundtrack Dean Man On Campus.

But the performance during which Bowie mimed to "Golden Years" on ABC's Soul Train in 1975 is by far the most significant. He was one of the only Caucasian performers invited onto the African American programme. [x] This performance, as Pegg states, "...came to be regarded as the unofficial video and was used to promote the single worldwide." And there is indeed a reason for this which O'Leary aptly surmises. He notes that this rendition is, "The essential video complement...Bowie is a wraithlike spiv who’s barely able to mime the words (it’s as if he’s hearing the song for the first time, and he still seems in character from The Man Who Fell to Earth) while the audience dances beneath him, as if communally denying his presence."

Indeed, the cocaine-addled Bowie is mesmerising to watch. Always the consummate performer, the last Bowie character, Thin White Duke, can already be detected in this early performance. He cuts a stark, pale figure against the groovy, dark audience. And this character is another reason this song is one of my favourites.

The Thin White Duke was an amalgamation of Bowie's cocaine drug-addled paranoid state, his musical genius, and his character of Thomas Jerome Newton from Nicholas Roegg's The Man Who Fell to Earth. This character would be the last Bowie ever created before performing as himself for the remainder of his life. The Wikipedia page described him as:

At first glance, [appearing] more conventional than Bowie's previously flamboyant glam incarnations. Sporting well-groomed blonde hair and wearing a simple and impeccably stylish, cabaret-style wardrobe consisting of a white shirt, black trousers, and a waistcoat, the Duke was a hollow man who sang songs of romance with an agonised intensity while feeling nothing, 'ice masquerading as fire'. The persona has been described as "a mad aristocrat", 'an amoral zombie', and 'an emotionless Aryan superman'. Bowie himself described the character as 'A very Aryan, fascist type; a would-be romantic with absolutely no emotion at all but who spouted a lot of neo-romance.'"And indeed, the darkness of The Duke's character was also a symbol for the similarly darkest period of Bowie's own life. In later interviews, Bowie admitted that he couldn't remember most of his time living in Los Angeles from 1974-1976 or even his performance on Soul Train due to his high dependency on cocaine. In 1983 Bowie described his experience living in La La Land:

It was unreal, absolutely unreal. Of course, every day that you stay up longer - and there's things that you have to do to stay up that long - the impending tiredness and fatigue produces that hallucinogenic state quite naturally. Well, half-naturally. By the end of the week my whole life would be transformedinto this bizarre nihilistic fantasy world of oncoming doom, mythological characters and imminent totalitarianism. Quite the worst. I was living in LA with Egyptian decor. It was one of those rent-a-house places but it appealed to me because I had this more-than-passing interest in Egyptology, mysticism, the Kabbalah, all this stuff that is inherently misleading in life, a hotchpotch whose crux I've forgotten. (Pegg, 2016)And later in 1997 he stated, "At some points I almost reached 80lbs. It was really, really painful. And also my disposition left a lot to be desired. I was just paranoid, manic depressive, it was all the usual emotional paraphernalia that comes with abuse of amphetamines and coke and all that.". And even at the time of Station to Station's release in 1976 he characterised the album as, "a plea to come back to Europe for me... one of those self-chat things one has with oneself from time to time." (Pegg, 2016)

Clearly time for a change, "Golden Years" marks the period of transition. It's nestled Bowie's American whirlwind of glam rock and plastic soul in the early 70s (as characterised in his albums Aladdin Sane (1973), Diamond Dogs (1974), and Young Americans (1975)) to his musical revolution and innovation in Berlin of art rock and world/ambient/electronic music during the late 70s (as characterised in his so-called "Berlin Trilogy" albums Low (1977), "Heroes" (1977), and Lodger (1979)). And the fact that this song straddles two very different periods in his career is exponentially fascinating. "Golden Years" makes a period of tension, inner turmoil, and change. It's the most exciting time in an artist's life - when they are ready to move onto something else. And the lyrics of "Golden Years" certainly illustrate all of these thematic concepts (as well as Bowie's strength as a writer).

A year ago, I convinced my temporary mentor, Dr. Aijian, to let me do a semester project on David Bowie's work. I decided to analyse the lyrics of every single song written by him from 1969-1983 and from 2002-2016 in his canon discography as a solo artist. And truthfully, the lyrics are the reason I fell in love with this song above all other Bowie songs.

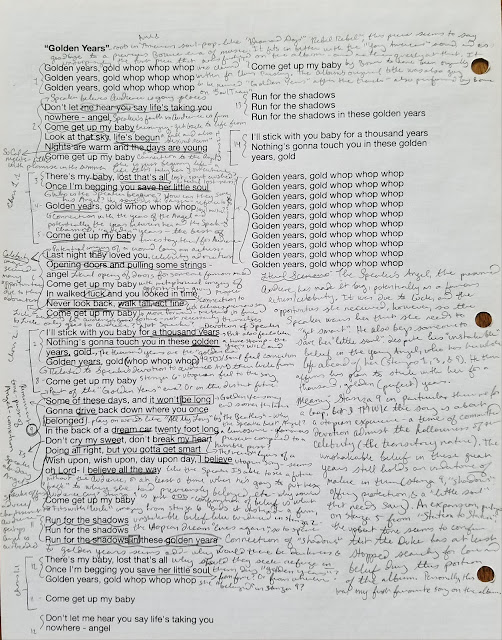

|

| My original analysis of "Golden Years" from my Spring 2016 Torrey Project |

The tantalising mix of utopia with darkness is perfectly blended together. I love that the song on the surface seems peppy and upbeat. These are Golden Years where "life's begun/nights are warm and the days are young". But a deeper look at the lyrics reveals a darker reality.

At first, everything seems hunky dory. The singer refers to how the audience of the song, whom he refers to as his 'angel' and 'baby', is currently in the middle of their 'Golden Years'. They are potentially a famous, successful individual who has the public and the producers eating out of their palm. This is evidenced by the speaker when he croons, "Last night they loved you/Opening doors and pulling some strings//In walked luck and you looked in time/Never look back, walk tall, act fine". Furthermore, this is supported by the speaker's promise of devotion which is repeated in the chorus of the song, "I'll stick with you baby for a thousand years//Nothing's gonna touch you in these golden years, gold".

But wait a second - something seems odd. What could the speaker's baby need protection from if the years are actually a "golden" utopia of existence? Not only that, but the speaker repeatedly intermixes the repeating statement "Golden years, gooo-ohhh-oollldd whop whop whop" with a foreboding plea, "There's my baby, lost that's all/Once I'm begging you save her little soul".

Indeed, this is expanded upon in the verse:

Some of these days, and it won't be long

Gonna drive back down where you once belonged

In the back of a dream car twenty foot long

Don't cry my sweet, don't break my heart

Doing all right, but you gotta get smart

Wish upon, wish upon, day upon day

I believe oh Lord- I believe all the wayOnce again, the veneer of golden years is slowly revealed to be just that - an illusion. Why else would the speaker be warning about a when his baby will be crushed back down "where [they] once belonged"? Why else would he be offering comfort for a time when they will be crying? Why would he implore his baby to "get smart" about their place in the presumed paradise? And why else would he be desperately clinging to his belief in, and appealing to the Lord?

This darkness is further confirmed by the end of the song when the speaker threateningly, yet paradoxically at the same time comfortingly, repeats, "Run for the shadows/Run for the shadows/Run for the shadows in these golden years". The fact that the shadows are a place for refuge is damning - and telling. "Golden Years" is not about a perfect existence, but a multi-faceted, nuanced one which contains darkness along with the light. Finally, the song spirals out into a hypnotic ending, repeating "Golden years, gooo-ohhh-oollldd whop whop whop" until it fades out.

O'Leary writes an excellent review of the song thusly:

...it’s not just “Son of ‘Fame’,” as it’s structurally and lyrically more nuanced than the earlier single. “Golden Years” opens as a blessing, its title phrase whispered and cooed, and its opening verses find Bowie in huckster mode, his vocal a series of considered appeals: “don’t let me hear you say life’s taking you nowhere!” he begins, a run of sharp monosyllables slowly descending in tone; the swaggering consonance of “in walked luck and you looked in time“; the paralleling of the highest and lowest notes of the song—Bowie’s octave leap to “AN-gel,” matched, four bars later, with the low “days are yuh-uh-ung.”

This is music for a fraudulent boom time, an advertisement placed in the gold rush. But the offer of “golden years” is entirely individual, not communal—the promise is made to one person, to be anointed, put in the back of a limousine and sealed off from the street. It’s not so much the promise of riches as it is of removal: nothing’s gonna touch you; never look back. Yet “Golden Years,” as it continues, seems to erode while the singer watches. A rap of materialist promises becomes a sudden prayer to God, followed by Bowie murmuring “run for the shadows” over and over again. And where Bowie once caressed the words “golden years,” now he pinches them, drags them out, distorts them—“years” in particular becomes a strangled curse.Station to Station may never reach the dizzying heights of the famed "Berlin Trilogy" for influencing decades of music to come, be cited as an integral part of creating an entire sub-genre of music like The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars (glam rock is indeed a gift), or even be counted as his first American hit (that pleasure would belong to the track "Fame" co-written with [yes, that] John Lennon). But as Pegg describes Station to Station, the album is, "now regarded by many as one of Bowie's most important works, a multi-textured experience illuminated, but not diminished, by an awareness of the anguish that attended its creation." "Golden Years" is an integral part of highlighting that anguish while at the same time providing an excellent single that can be put on repeat for hours (like it currently is while I write this piece). And I can guarantee you that you will never tire of it.

So overall, the structural nuance, thematic development, and smooth vocal work make for a fantastic piece in which The Thin White Duke lulls you into a hypnotised trance - at once enamoured and intoxicated with both song and singer. As Bowie himself stated about his work on Station to Station, "It had a certain magnetism that one associates with spells. There's a certain charismatic quality about the music...that really eats into you. I still don't know what I think about that album. I find it, at times, probably really quite beautiful, and at other times extraordinarily disturbing." (Pegg, 2016) Eat your heart out, Major Tom.

No comments:

Post a Comment